By Tom Fleming

letters@irishecho.com

What is the most important argument in American history? The quarrel between North and South that led to the million dead of the Civil War?

The struggle for the civil rights of black Americans? The perpetual conflict between the haves and have-nots?

All these things have roiled the nation. Some of them are still disturbing our political equilibrium.

But there is one conflict that most people do not recognize, partly because it began so early and partly because it can take - and has taken - several forms. It is the clash that first divided - and then made enemies - of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

Surprised? So was I when I read in a congressman’s diary that he visited Mount Vernon after Washington died. Martha Washington told him the two worst days of her life were the day George died and the day Jefferson came to pay his condolences. That is when I started digging into this forgotten feud. I soon decided it was our most important argument because it involves the basic structure of the American government.

Thomas Jefferson was in France, serving as America’s ambassador when George Washington, James Madison and other gifted men created and ratified the Constitution. At the heart of the document was a new office, the presidency, with powers co-equal to Congress.

Washington was the chief advocate of this innovation; he had seen how poorly the Continental Congress performed during the Revolutionary War, without a strong leader to unify their policies.

Thomas Jefferson disliked the Constitution. He was even less enthusiastic about the presidency.

He thought they were both too strong.

Together they represented a threat to American liberty. He made it clear that this was his primary value. He did not expect the Constitution or the union to endure very long. He saw nothing wrong with western states seceding and forming a separate nation. At one point he argued that every generation should write a new constitution. James Madison talked him out of that wild idea.

When Jefferson returned to America and became Washington’s secretary of state, the two men clashed repeatedly over their differing opinions. For Jefferson the dangers were spelled out in Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton’s policies.

He sought to unify the nation’s economy around a government controlled central bank that would pay off the Revolutionary War’s debts and encourage commerce and manufacturing.

He argued there were “implied powers” not stated explicitly in the Constitution that enabled the federal government to do such things. Washington agreed with him. Jefferson saw these policies as ominous steps toward a tyrannized nation, probably ruled by a king.

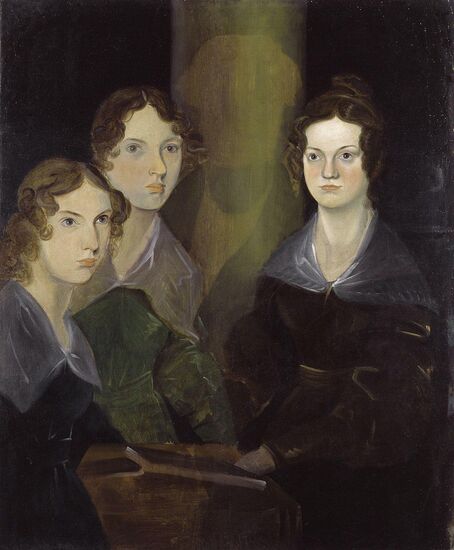

Author Thomas Fleming.

Complicating matters was Jefferson’s hatred of Great Britain and his enthusiasm for the French Revolution. Washington did not share either sentiment.

After peace and independence were secured, he was ready to deal with Britain as he would with any other foreign country. When the French revolution fell into the hands of radicals who beheaded King Louis XVI and began massacring thousands of innocent people, Washington saw France as a menace to freedom everywhere.

After several tense face to face encounters, Jefferson realized he could not change Washington’s mind and resigned from the government.

But he remained the active leader of a political party that opposed the Washington administration’s foreign and domestic policies. He persuaded Madison, once Washington’s closest advisor, to act as his right hand man in Congress.

When Jefferson became our third president, he was determined to undo Washington’s presidency. He called his administration “The Revolution of 1800.”

He praised Washington as “our first and greatest revolutionary character,” but ignored his presidency.

Jefferson was determined to make Congress the dominant voice in the federal government. He accomplished this in several ways. He abandoned Washington’s annual speeches to Congress, reporting on the government’s problems and successes. Instead, Jefferson’s reports were read by a clerk.

Even more important was the way Jefferson worked behind the scenes with congressional leaders to get his polices accepted. He soon created the illusion that Congress was running the country.

He was tremendously helped by a stroke of good fortune - France’s decision to sell the Louisiana Territory to the United States - thus adding a third of the continent to the nation. Thereafter Jefferson’s reputation rivaled, and even exceeded, Washington’s.

In times of crisis, however, some presidents invoked Washington’s tradition of strong presidential leadership.

In 1833, Andrew Jackson crushed South Carolina’s attempt to secede from the Union by invoking the presidency’s implied powers.

The Civil War made Abraham Lincoln the strongest president since Washington. The man from Illinois had no hesitation about wielding unprecedented power to deal to rescue the Union. He suspended habeas corpus and other rights, issued the Emancipation Proclamation, and dozens of executive orders, without consulting Congress.

When an assassin killed Lincoln, Congress, already resentful at his assertion of the presidency’s implied powers, seized control of the federal government.

It abandoned Lincoln’s policy of reconciliation and set about punishing the South for the Civil War. For the next forty years, weak presidents and an emboldened Congress became the rule.

The old adage, power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely, came into play. Congress became the home of political bosses whose chief interest was their own enrichment.

Not until Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901 did the strength and leadership Washington and Lincoln brought to the office reappear.

By that time, America was on the brink of a revolution. A wealthy upper class and an impoverished lower class were regarding each other with growing hatred.

Roosevelt began condemning “malefactors of great wealth.” He instituted anti-trust lawsuits against several businesses that had become brutal monopolies. He created national parks and national forests, reassuring people that some of America’s most attractive landscapes would always belong to everyone. He declared that his administration guaranteed a “square deal” to every working man and woman.

Someone asked President Roosevelt where he got the authority to act and speak so independently of Congress. He cited “the Jackson-Lincoln” theory of the presidency.

There was no mention of George Washington. It was mournful evidence that Thomas Jefferson’s determination to obliterate Washington’s presidency had been all too successful.

A few years after Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson became president. He had written a book, “Congressional Government,” which severely criticized this distortion of the founders’ Constitution.

Wilson restored one of President Washington’s most important innovations, his annual speech to Congress. A superb orator, Wilson was soon persuading Congress to pass badly needed legislation, such as the creation of the Federal Reserve banking system, which returned control of the nation’s finances to the government.

Another strong president who invoked the presidency’s powers was Franklin D. Roosevelt. Confronting the crisis of the Great Depression, he relied on the veto to force Congress to follow his leadership, invoking this power 641 times, more often than all his predecessors combined.

The wars and recessions of the rest of the Twentieth Century added enormously to the presidency’s power. By the 1960s, presidents asserted the right to block or “impound” Congress’s attempt to spend money for dozens of federal programs.

President Richard Nixon carried this policy to an extreme that infuriated Congress. Exacerbating his relationship to the lawmakers was Nixon’s determination to win the war in Vietnam – a policy that the Democratic majority in Congress opposed.

In 1972, Nixon won reelection in one of the greatest landslides in American history. It was graphic evidence of the presidency’s awesome power.

The whirlpool of extreme emotions swirling around Nixon exploded when a political burglary in the Watergate apartments revealed a president who was all too ready to lie and conceal evidence.

Nixon’s resignation to avoid impeachment led directly to another era of congressional government. Congress passed the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Act, which made the lawmakers the sole judge of how much they could spend.

It was the beginning of unchecked deficit government that may yet imperil the financial stability of the nation and the world.

The presidents who have succeeded Richard Nixon have repeatedly found themselves challenged by an aggressive Congress. America has the only legislature in the world that claims the right to interfere in their country’s foreign policy. Again and again we have seen recent presidents confronted by the central issue that divided Thomas Jefferson and George Washington.

There is no easy solution to this dilemma. Both sides must work out a balance that will enable the federal government to function. Until recently, President Barack Obama and the Republican majority in Congress have been disinclined to make any concessions. Perhaps there is an answer in a little known aspect of the Great Divide.

Toward the end of James Madison’s life, he had a profound change of mind and heart. He repudiated Jefferson’s approach to government. He addressed Congress directly, urging them to create a trained army and navy.

Lack of both had almost cost us our independence in the War of 1812. He urged the creation of a central bank. He recommended Washington’s Farewell Address as important reading, even though it contained a fierce criticism of Thomas Jefferson’s worship of the French Revolution.

He called on all Americans to regard the Union as the crucial value of their government.

One might say that Madison had abandoned the divisive ideology of Monticello, and returned to the sunny porch of Mount Vernon as George Washington’s friend and admirer.

It is a journey that all Americans can and should take now and in the uncertain future. Never have we had a greater need for a new appreciation of George Washington’s approach to the presidency.

Author and historian Thomas Fleming’s new book, “The Great Divide: The Conflict Between Washington and Jefferson That Defined A Nation" is published by Da Capo Press, Boston.