Between the Lines / By Peter McDermott

John F. Fitzgerald. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

One of the big stories of the past few weeks has been Donald Trump’s comments about Mexican immigrants in general and Jeb Bush’s wife in particular.

Someone would have to be living without electricity in the Adirondacks to not know that this brouhaha has pushed the billionaire to the front of the GOP 2016 primary field.

Naturally, we here at the Echo are hard at work looking for the Irish angle. He does own that golf course in County Clare, which is a good start. And his mother was a Scottish immigrant – so there’s that, if Pan-Celticism is your thing.

But here’s what we’re really interested in: given that political figures will bend over backwards to patronize someone’s identity, just how might The Donald himself pitch an appeal based upon a voter’s heritage? We can’t help feel it would be open to ridicule, at the very least. Because if you’re Irish, to take the example close to hand, you couldn’t be unaware that your group was the victim of Trumpism in its earlier manifestations.

The upside of this for his admirers, however, is that the targeting of an immigrant group is as American as apple pie, especially if that group is rapidly growing in numbers and can be depicted as criminally-inclined.

Inevitably, this is a theme that former Boston Globe reporter Gerard O’Neill considers in his very interesting history, “Rogues and Redeemers: When Politics Was King in Irish Boston.”

Early on in his story, the Irish population of Boston exploded from one in 50 to one in four. “Mortified Yankees found themselves stepping over or dodging drunken immigrants in the once safe and sedate streets of Boston,” O’Neill writes. “It became the core of the Yankees’ overly broad case against the Irish – that they were shiftless drunkards who were a dead weight on the tax base, now stretched to pay the ever-expanding police and fire and hospital budgets.”

He quotes the Harvard historian and notorious anti-Semite Henry Adams writing in later years to a friend: [P]oor Boston had run up against it in the form of its particular Irish maggot, rather lower than the Jew, but with more or less the same appetite for cheese.”

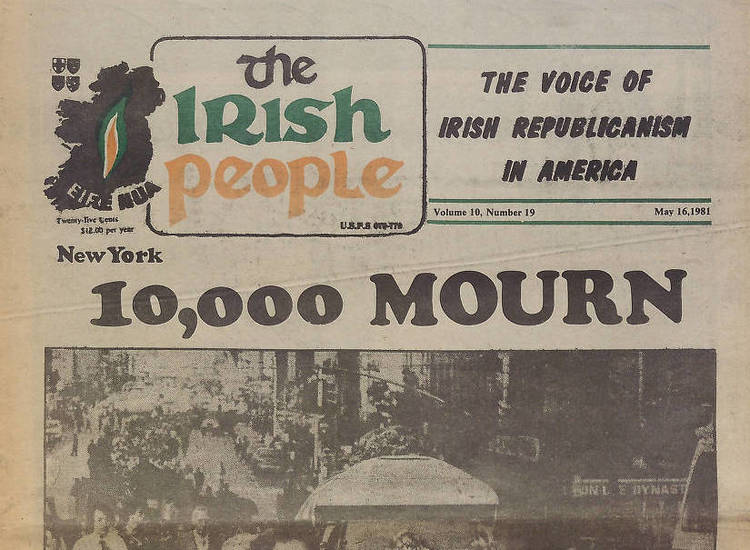

O’Neill tells how the Irish became organized enough over the decades to challenge for political power. Along the way, a couple of Irish-born pols made it to mayor with Yankee approval. Then in 1905, a product of the ghetto, John F. Fitzgerald, ascended to the office on his own terms, only to be succeeded by another, James Curley, in 1914.

During a stint in Congress in the 1890s, Fitzgerald, known as “Honey Fitz,” had opposed the growing movement to restrict immigration with literacy-test trickery.

Taking the other side was Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, a friend of Adams and a fellow historian. (Fitzgerald and Lodge’s grandsons would face off in a Senate race in 1952 and were on the opposing tickets in the 1960 presidential election.)

Henry Cabot Lodge. NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY

Says O’Neill: “Taking the measure of the burgeoning Irish in Boston, [Lodge] decided that they could stay in his country, but Italians and Jews had to go. They were the new indigestibles, and Lodge began his first push for the literacy testing…”

The issue of crime was raised time and again from the early 1880s. The New York Times warned in 1884 that brigandage had been until recently the “national industry” of Italy’s Southern provinces.

“It is not strange that these immigrants should bring with them a fondness for their native pursuits,” the Times writer said. “A band of brigands would find the rookeries of Mulberry Street much more comfortable than the Calabrian forests, and much safer. The brigands, when pursued by the police, could pass from roof to roof, lie in ambush behind chimneys, defend narrow scuttles against a vastly superior force, and finally make their escape with much greater ease than could a band surrounded in an Italian forest by a regiment of troops. When brigandage becomes fully organized here wealthy citizens will constantly be captured and held for ransom.” (Salvatore J. LaGumina has a book full of this kind of stuff in “Wop! A Documentary History of Anti-Italian Discrimination.”)

Italian-Americans have been battling mafia and brigandage stereotypes in the 125 years since. Such efforts are never easy. And actual facts don’t help much – such as the one pointed out by a U.S. correspondent in the Daily Telegraph, a conservative London broadsheet: the percentage of non-citizens in U.S. prisons is lower than the percentage of non-citizens in the population as a whole. For it’s never really about crime or the legal status of someone seeking available work in a job market. Rather, it’s: “They’re not like us and would find it very difficult, if not impossible, to assimilate” or “They’ll drag our civilization down to their level.”

O’Neill reproduces a conversation that Fitzgerald recalled he had with Senator Lodge (quite possibly invented, though it did encapsulate their views).

Lodge: “You are an impudent young man. Do you think the Jews and the Italians have any right in this country?”

Fitzgerald: “As much as your father or mine. It was only a difference of a few ships.”

Eventually, Lodge’s side had its way with the Immigration Act of 1924. But, in the category of revenge is a dish best served cold, 90 years on, there is an Italian/Jewish majority on the U.S. Supreme Court. We might reasonably speculate, then, that one day – after Trump has joined Ozymandias in antiquity – children and grandchildren of today’s undocumented immigrants will be appointed to that august tribunal.

![J._F._Fitzgerald[1]](https://www.irishecho.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/J._F._Fitzgerald1-222x300.jpg)