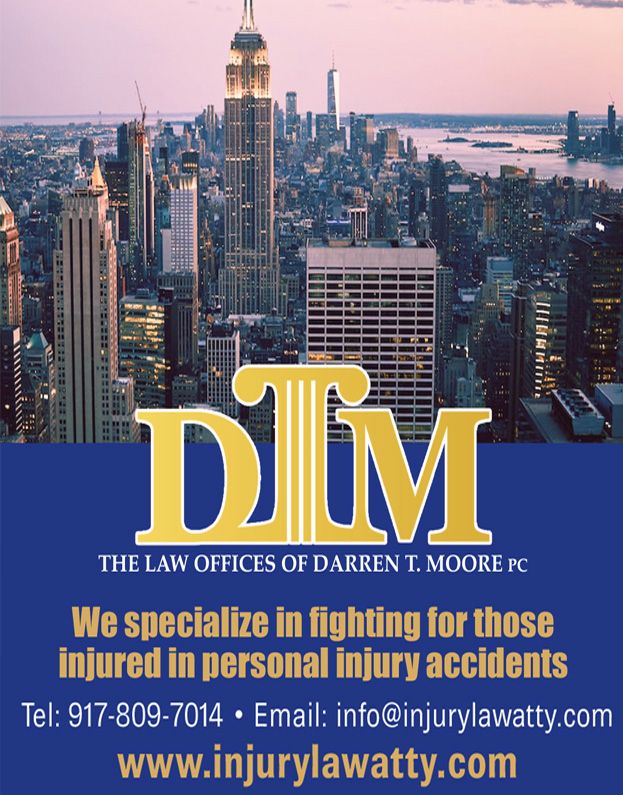

[caption id="attachment_67672" align="aligncenter" width="600" caption="From left: Orlagh Cassidy, Rachel Pickup, Aedin Moloney and Annabel Hagg in "Dancing at Lughnasa." Carol Rosegg"]

Dancing at Lughnasa By Brian Friel • Irish Repertory Theatre, 132 West 22nd St., NYC (212) 727-2737 • Through Dec. 11, 2011

Is "Dancing at Lughnasa" Brian Friel's finest play to date? "Aristocrats," if done correctly, is more moving and more resonant. "Philadelphia, Here I Come," the play that launched Friel's career and made him famous, is probably the favorite of any actor who ever played in one of its many productions.

"Dancing at Lughnasa," however, which opened on Broadway in October, 1991, and won the 1992 Tony Award for Best Play, has very special significance for the playwright: the five unmarried women at the center of the plot are based on and named for Friel's own mother and her sisters.

He used to refer to them as "those five brave Glenties women," and, for the purposes of the play, he has renamed them "the Mundy sisters," and placed them in a dwelling some two miles outside the village of Ballybeg, the town he "created," and where he's placed so many of his plays.

The Irish Repertory Theatre's admirable production marks the play's 20th anniversary.

In life, as in the play, which takes place in the early autumn of 1936, the sisters lived in a modest cottage in Donegal. In Friel's rendering of the tale, which has strongly autobiographical elements, the household revolves around Michael, the seven-year-old "lovechild" of one of the sisters, Chrissie. Almost as central to the playwright's intentions is the family's sole brother, a priest, known as Uncle Jack. He has recently returned to Ireland, his memory failing and his mind somewhat shattered after serving for 25 years in a leper colony in Uganda.

Friel's title refers ato the Harvest God, Lugh, and the season he represents, as the women adjust to their eldest sister Kate's having lost her teaching job, an event which changes all of their lives forever.

Uncle Jack's return to his sisters' world is motivated, as Friel's narration subtly suggests, by an overidentification with his African surroundings, and with one African individual in particular.

Kate's having lost her teaching job, thus depriving the sisters of their primary income, is also linked with their brother's return from Africa, although Friel leaves the specific details unexplained. Michael Countryman is excellent as the returned priest.

More than any other of his plays, Friel has crafted "Dancing at Lughnasa" as a work of secrets and suggestions. A detail which bothered some of the critics who wrote about the original production had to do with the actor cast as the adult Michael being required to carry a rather heavy, but beautifully written narrative load, and, at the same time, playing his character at age seven, unseen by any of the sisters, except for his Aunt Maggie, with whom he has a particularly close relationship.

In Charlotte Moore's fine production, Ciaran O'Reilly's Michael is a particular triumph, with this always reliable actor absolutely at the top of his form, playing his character, as a child and as an adult, with a grace which eliminates any problems the role itself may present.

As Gerry Evans, who fathered Michael, Kevin Collins is a standout, as is Orlagh Cassidy as the grim teacher, Kate, the sisters' primary backbone. The sisters are outstanding, including Jo Kinsella's free-spirited Maggie, Annabel Hagg's lovely Chris, Rachel Pickup's sober, restrained Agnes, and Aedin Moloney's vaguely damaged Rose.

Moore has done wonders with a reasonably difficult play. The choreography provided by Barry McNabb makes a solid contribution, since the text calls for a fair amount of dance.

"Dancing at Lughnasa" is, beyond a doubt, one of the Irish Repertory Theatre's best recent productions.