Eva the Chaste By Barbara Hammond • With Aedin Moloney • Directed by John Keating • Fallen Angel Theatre Company, lurman Theatre, Theatre Row, NYC • Tickets: (212) 239-6200 • Through July 24, 2011

Perhaps it's significant that when actress and playwright Barbara Hammond, who is the youngest of a large family, comes up with a play, it's a solo piece with a woman as its solitary speaker. The 70-minute, intermissionless result, "Eva the Chaste," will be on view at the Clurman Theatre through July 24.

Hammond is fortunate in having the remarkable Aedin Moloney, for whom the play was written, and whose company, Fallen Angel Theatre, is producing it, on deck to bring her Eva to life, and the skilled actor-turned-director, John Keating, to stage it with clarity and impact.

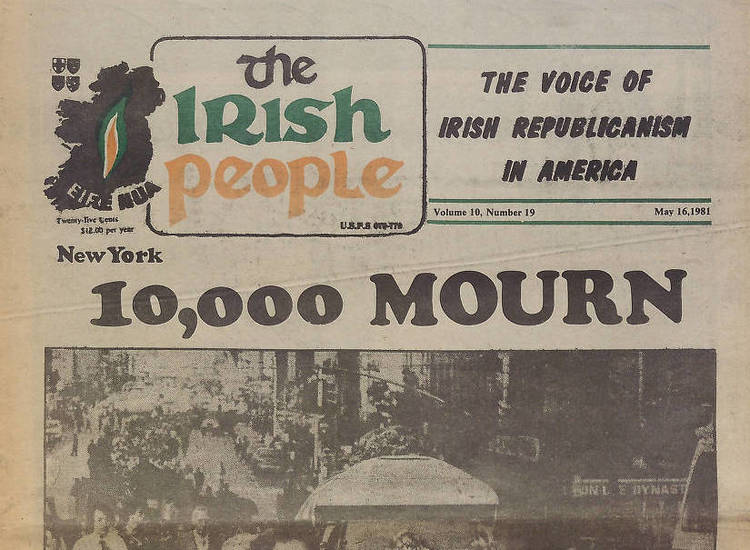

Actress Moloney, the daughter of Paddy Moloney, the durable force behind The Chieftains, who supplied music for the show, is slight and might almost be described as being fragile-seeming, but don't be deceived. She has a rare power at her command, as was evident a year or so ago when she appeared in Paula Meehan's "Cell," playing the most violent of four women sharing a space in a Dublin prison.

Her performance, guided then as now by Keating, was so bizarrely powerful that many of the members of her audiences, friends included, were afraid to speak with her when the show was over.

The printed rehearsal text of "Eva the Chaste" locates the play as taking place "on the steps of a semi-detached house in Rush, a seaside market village at the end of the Dublin bus line."

The text doesn't call for much of a scenic design, but Melissa Shakun has provided a sort of skeletal set, with the suggestion of a window here, a door there and a step or two leading to a little platform which primarily remains unused.

The play's title is a joke: Eva's mother once said she hoped her daughter would be "chaste," and the heroine converted the word to "chased," as in "pursued." The word "chaste" is possibly unfamiliar to some of the play's audience, but the title comes off as a slightly tacky joke, particularly for a work which deserves better.

Eva has left Ireland and her family and gone to live in Paris, from which she returns because of the illness and gradual decline of her aging parents. She comments, in a minor complaint, that she doesn't even bear the name of a Catholic saint. "You'd never say Saint Eve," she says. Meanwhile, her sister, Theresa, has two, since there are, in fact, two saints named Theresa, one of them being the Little Flower.

Eva adds that "I got Adam," and that the pair were "turfed out of Eden under remarkably underhanded means."

Hammond has attached a brief lift from Albert Camus to her play as a sort of statement of dedication. "The only way to deal with an unfree world," she quotes, "is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion." The irony suggested by Camus' comment is that Eva, at best, seems unlikely ever to become really free, which may be the playwright's point. Hammond's writing is solid, and sometimes considerably more than that, particularly when Aedin Moloney is hitting on all eight cylinders, as she so very often is in "Eva the Chaste."

Fallen Angel's future plans include an evening of one-act plays adapted from the works of novelist Colum McCann, who won last year's National Book Award for "Let the Great World Spin." Fallen Angel, with any luck at all, should have a splendid future.