While we are all heartened by the productive cooperation in Northern Ireland between the Sinn Fein First Minister Michele O’Neill and the DUP Deputy First Minister Emma Little Pengelly, many younger people have no understanding of the long struggle by so many to achieve peace and equality after years of repression and discrimination.

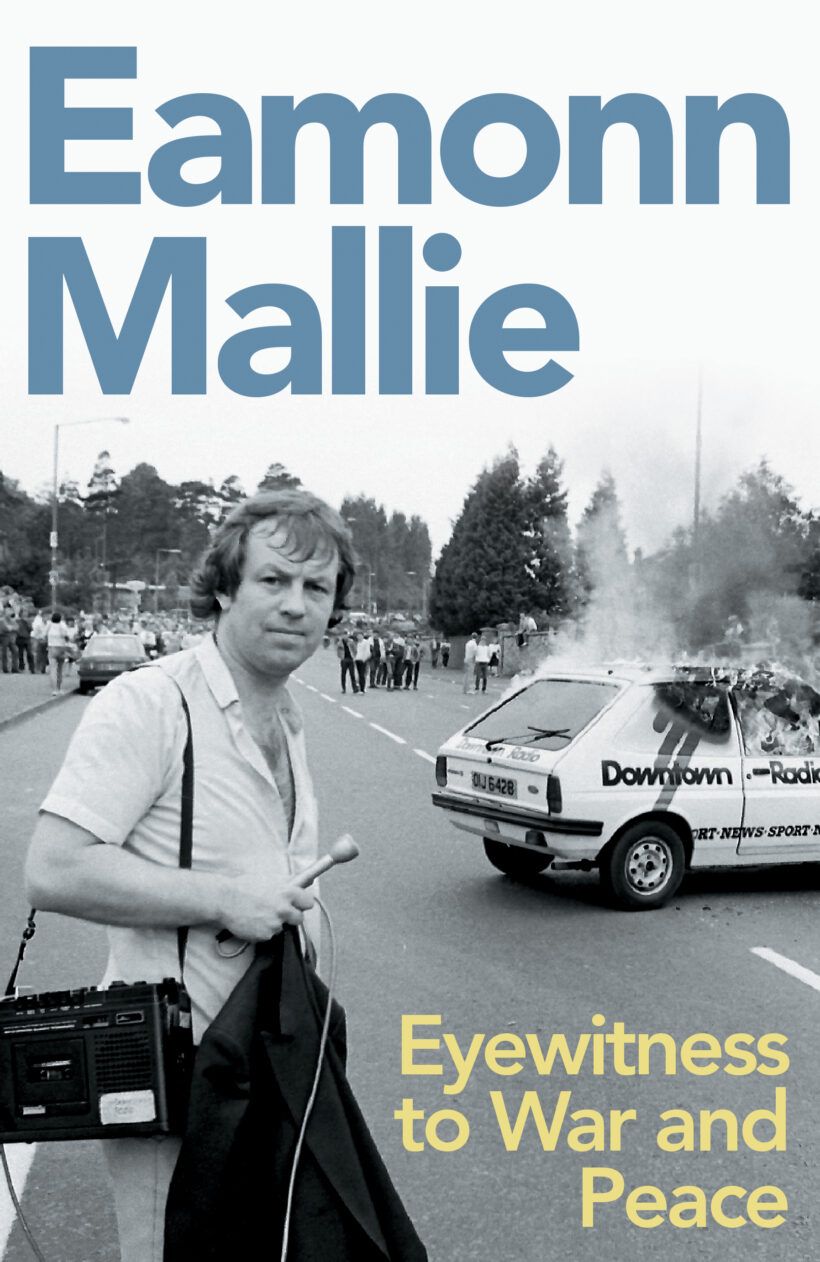

Eamonn Mallie, a superb and fearless radio journalist for 40 years, has written a new fast-paced book which tells this story in an exciting and very readable style.

"Eyewitness to War and Peace," which has now been published in the U.S., reveals the secret and relentless talks over decades that ultimately ended the bloodshed to create a society that recognized the equal rights of nationalists and unionists.

From the 1970s onwards, Mallie was the voice of Downtown Radio Belfast as it broke the mold with news headlines every half hour and news on the hour. At a time when people were being regularly bombed and murdered, Mallie regularly risked his life by personally covering the atrocities, always seeking the truth and sticking his microphone up the noses of everyone from royalty to prime ministers, from paramilitary leaders to police chiefs and army generals.

I recall seeing Mallie in action at the signing of the historic Anglo-Irish Agreement by Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in Hillsborough Castle in 1985.

Ian Paisley and his violent followers were trying to break in to stop the signing of the Agreement because it gave Dublin a role in the running of Northern Ireland for the first time.

Eamonn Mallie.

Mallie asked Thatcher the key question: Was she willing to defeat these loyalist thugs when previous British Prime Ministers had caved in to them?

Thatcher did not reply to the question, but over subsequent months she and the RUC and British Army defended the Agreement against loyalist attacks, the first time a British government successfully defeated widespread loyalist resistance in the history of Northern Ireland.

Mallie, who was born and raised in South Armagh, says he was “always an admirer of Hume’s anti-violence and pro-European stance.” But he did not see this as a reason “to shun those who chose to take up arms” because he wanted to understand why they felt the need to use violence.

Mallie describes in vivid detail how John Hume, despite all the setbacks and criticism, persevered in the secret Hume Adams talks which set the scene for the negotiations that led to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. Hume told Mallie that he believed Gerry Adams was looking for a way to move to an exclusively political campaign for nationalist rights and a united Ireland.

Mallie recalls how the IRA had reached the conclusion, as had British General Jimmy Glover, that neither side could win, that the British could not be bombed out of Northern Ireland, and that the IRA could not militarily be defeated.

Nevertheless, Mallie muses, “what continues to baffle me is how the Sinn Fein leadership, Adams and McGuinness, ever managed to convince the IRA to call a cessation of violence given the endless turmoil in its ranks.”

Undoubtedly, the skilled leadership and ultimate vision for a new Ireland that these two men shared was a significant factor, but another was that Sinn Fein realized it could succeed in electoral politics when ailing hunger striker Bobby Sands was elected to the British parliament in 1981.

The election of Tony Blair as Prime Minister and Bertie Ahern as Taoiseach in the late 1990s gave the slow peace process some fresh impetus. They, along with President Clinton, decided to use their immense political capital to go all out for an agreement.

As Blair said at the Queen’s University GFA 25 events last year when the three old pols had reconvened: “We were too young to be cynical about the prospects of peace.”

As Mallie writes, the Good Friday Agreement almost didn’t happen but the political leaders made sacrifices and took risks for the sake of peace. As Senator George Mitchell has said, everyone had to have the courage to make compromises to reach peace.

"Eyewitness to War and Peace" is essential reading for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of Northern Ireland’s divided and violent past and its hopeful future today.

"Eyewitness to War and Peace" is published by Merrion Press and is available on Amazon. Ted Smyth, a former Irish diplomat and business executive who lives in the United States, is a member of the Ad Hoc Committee to Protect the Good Friday Agreement.