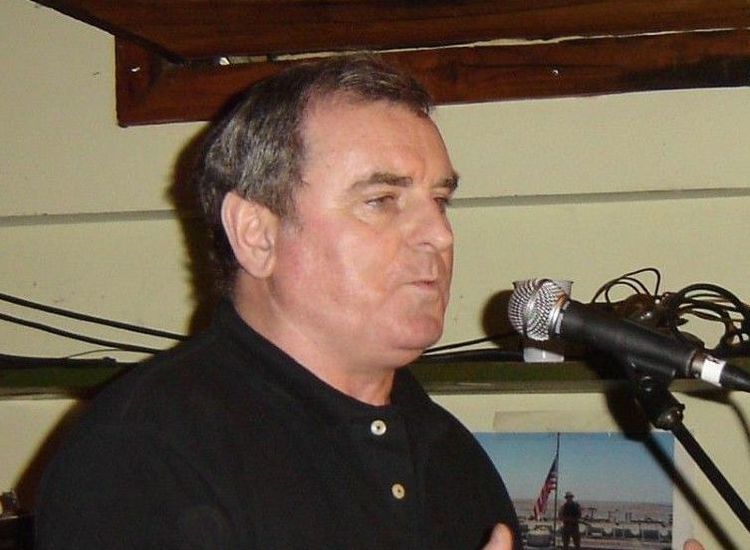

John Horgan, the coauthor of “Irish Media: A Critical History,” was appointed Ireland’s first press ombudsman in 2007.

Page Turner / Edited by Peter McDermott

The Freeman’s Journal stuck with the post-divorce Charles Stewart Parnell for months after that had been the commercially and politically prudent thing to do, and it “suffered enormously” as a result, though later its “vestigial anti-clericalism attracted the admiration of James Joyce,” say authors John Horgan and Roddy Flynn in their “Irish Media: A Critical History.”

During the next big national split – over the terms of the Treaty 30 years later – the Freeman’s Journal sided with the majority and indeed of the dailies was the most enthusiastic backer of the Provisional Government. But that only led to more pain.

“When it published in March 1922 accurate but uncomplimentary information about the inner workings of the republican movement, which had been deliberately leaked to it by the authorities,” the authors write, “armed republicans entered its center-city premises in Dublin and destroyed the machinery with sledge-hammers.”

As it happened, the 160-year-old Journal’s last chance to survive as a paper was a plan by anti-Treatyites to buy it. Instead in 1924, the Irish Independent stepped in and incorporated the title, which continued to appear on its editorial page masthead into the 1990s. And this – the Civil War and its aftermath – is more or less where Horgan and Flynn’s story begins, although the revised edition (it was first published in 2001) extends its survey back to the 17th century.

The Independent proved remarkably adept at following shifts in popular nationalist opinion, as well as protecting and expanding its market share. It was increasingly pro-Sinn Féin and pro-separatist from 1916 onwards and supported the Treaty, but it also took heed of boycotts in the republican heartlands of the south, southwest and west pushing for greater balance in Civil War coverage.

The Free State constitution supported the usual Western-style freedoms, including freedom of expression, with the qualification “for purposes not opposed to public morality.” After meeting with a deputation of Catholic bishops in 1926, Justice Minister Kevin O’Higgins established the Committee on Evil Literature. The Independent was vociferous in its support, “its mass circulation more at risk commercially from British competition than that of the Irish Times,” which, say Horgan and Flynn, attempted “to reconcile its liberal Protestant ethic and demonstrably middle-class concerns.”

The authors’ narrative looks at the relationship between Irish media and Irish politics, society, culture and the economy up to the present-time, which sees the “remaining stalwarts” – RTÉ, the Irish Independent, the Irish Times and many local papers – “experiencing irrevocable change.”

Horgan is particularly well-qualified to tell the story. After his early career as a journalist, he served for two terms in Seanad Eireann. He was then elected as a Labour Party member of Dáil Eireann for one term and briefly sat in the European Parliament, before embarking on a full-time academic career. He is emeritus professor at the School of Communications, Dublin City University (where his “Irish Media” coauthor Flynn is chair of film and television studies). He served, too, from 2007 through 2014 as Ireland’s first press ombudsman.

A prolific author, Horgan’s works include studies of three of 20th century Ireland’s most fascinating political figures: “Seán Lemass: The Enigmatic Patriot”, “Noel Browne: Passionate Outsider” and “Mary Robinson: An Independent Voice.”

IE: What is your writing routine? Are there ideal conditions?

John Horgan: When I'm writing, I lose all sense of time and hide myself away in my study. My family is not always best pleased. But I love wrestling with words and language until I get everything more or less into the shape I want it to be in. And I usually have to remind myself that, even though the next version of what I'm writing might be even better, the publisher, editor, or reader are waiting.....

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

For non-fiction (I haven't written any other kind), write about what you know and do not be too proud to accept that you may not be the world's greatest expert on anything. Write purposefully and revise frequently (especially if you are using a computer, which doesn't have as good a memory as you have). But beware of revising or editing on-screen: that generates prolixity and complexity which is often a barrier to good communication. So revise on hard copy first, in pen.

Name three books that are memorable in terms of your reading pleasure.

“Bitter Freedom: Ireland in a Revolutionary World 1918-1923,” by Maurice Walsh, another journalist-turned academic with an enviable gift for bringing vividness and relevance to contemporary history. “Ireland, 1912-1985: Politics and Society," by Professor Joe Lee. A multi-faceted masterpiece. What more can I say? "Puckoon," by Spike Milligan. A wacky, fake stage-Irish novel by a master of comedy and absurdity who was always proud of his Irish ancestry.

What book are you currently reading?

“De Valera: Rise 1882-1932,” by David McCullagh. Utterly absorbing - and superbly researched.

Is there a book you wish you had written?

The Bible.

Name a book that you were pleasantly surprised by.

Anything by Alan Furst about espionage in war-time Europe.

If you could meet one author, living or dead, who would it be?

Laurence Sterne, the author of “Tristram Shandy,” master of the picaresque and the fabulous.

What book changed your life?

They all did, in different ways, but the one I'm still wrestling with, because it asks me to change my life in ways I instinctively find too challenging, is the New Testament, and in particular the passage on the Beatitudes.

What is your favorite spot in Ireland?

Anywhere in West Cork.

You're Irish if...

You have learned that even if the pot at the end of the rainbow contains nothing more exciting than loose change, it's still worth looking for.

"Irish Media: A Critical History" is published by Four Courts Press (fourcourtspress.ie) and available in paperback in the U.S.